The recent tragic shootings in Buffalo, N.Y., Uvalde, Texas, Tulsa, Okla. and elsewhere have brought mass murders in the U.S. to the fore of public attention. For many, the overriding questions are why the U.S. murder rate is by far the highest of any developed country and what can be done to reduce it? Democratic lawmakers see gun control as a critical component to a solution, while Republicans contend that it will not make much difference and that gun ownership is protected by the Constitution.

What is not in dispute is the affinity many Americans have for firearms. In 2018, U.S. gun owners possessed 393 million weapons, according to the Small Arms Survey, a Geneva-based organization. America is the only country with more civilian-owned firearms than people – 1.2 firearms per resident – which far exceeds other developed countries. Moreover, the gap is growing amid a gun-buying spree that began two years ago.

While both sides marshal purported facts to support their claims, much of what is reported on social media and other platforms is inaccurate or misleading.

For example, a viral meme following the Parkland, Fla., shooting in 2018 claimed that while the U.S. had the third-highest count of murders worldwide, the ranking would drop materially if five major cities that have stringent gun control legislation were excluded. But a fact check by the Poynter Institute found that dropping them from the U.S. total had little substantive impact on the homicide rate.

A report by Third Way, a center-left think tank, countered the contention by noting that per capita murder rates in 2020 were 40 percent higher in states won by Donald Trump than in those won by Joe Biden.

The findings of the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank, are more helpful in shedding light on what is happening. In a report titled, “What the data says about gun deaths in the U.S.,” John Gramlich reported the following findings based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data for 2020:

First, 45,222 people died from gun-related injuries. Of this total, 54 percent were death by suicide, while 43 percent were murders and 3 percent were classified as unintentional. Nearly eight in 10 murders in the U.S. involved a firearm.

Second, on a per-capita basis, there were 13.6 gun deaths per 100,000 people in 2020, the highest rate since the mid-1990s.

Third, the rate of gun fatalities per capita varies widely from state to state. Those with the highest rates included Mississippi, Louisiana, Wyoming, Missouri and Alabama.

Fourth, it is difficult to identify how many people are killed in mass shootings each year, because there is no single agreed definition for the term. But regardless of the definition being used, “fatalities in mass shootings in the U.S. account for a small fraction of all gun murders that occur nationwide each year.”

Fifth, handguns were involved in 59 percent of U.S. gun murders and non-negligent manslaughters, while assault weapons were involved in 3 percent of firearm murders. The remainder involved other kinds of firearms.

All told, what these and other research findings suggest is that the high rate of murders in the U.S. is correlated with much higher gun ownership, which accounts for 46 percent of the world’s civilian-owned guns. It is the equivalent of Willie Sutton’s response to the question, “Why do you rob banks?” His reply, “Because that’s where the money is.”

According to a New York Times article, Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Norway all had a culture of gun ownership. But their governments tightened restrictions in response to mass shootings, which have since decreased.

So, why is it more difficult to curb gun usage in the United States?

One explanation is the way the Supreme Court chooses to interpret the Second Amendment of the Constitution. It states that “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

As Amber Phillips of the Washington Post observes, the view that the Second Amendment extends to individuals’ rights (as distinct from military service) only became mainstream in 2008: The Supreme Court ruled in the case of District of Columbia v. Heller that Americans have the constitutional right to own guns in their homes, which reversed the District’s ban on handguns.

But two law clerks who worked for Justices Antonin Scalia and John Paul Stevens on the case claim the ruling is mistakenly used to block legislation: “Most of the obstacles to gun regulation are political and policy based; it’s laws that never get enacted, rather than ones that are struck down, because of an unduly expansive reading of Heller.”

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court is about to hear a case that will decide whether the Second Amendment includes the right to bear arms in public spaces. Some observers anticipate that the ruling could knock down a New York law requiring people to show “proper cause” when applying for a gun license. If so, attempts to strengthen background checks to obtain a gun license would be dealt a further blow.

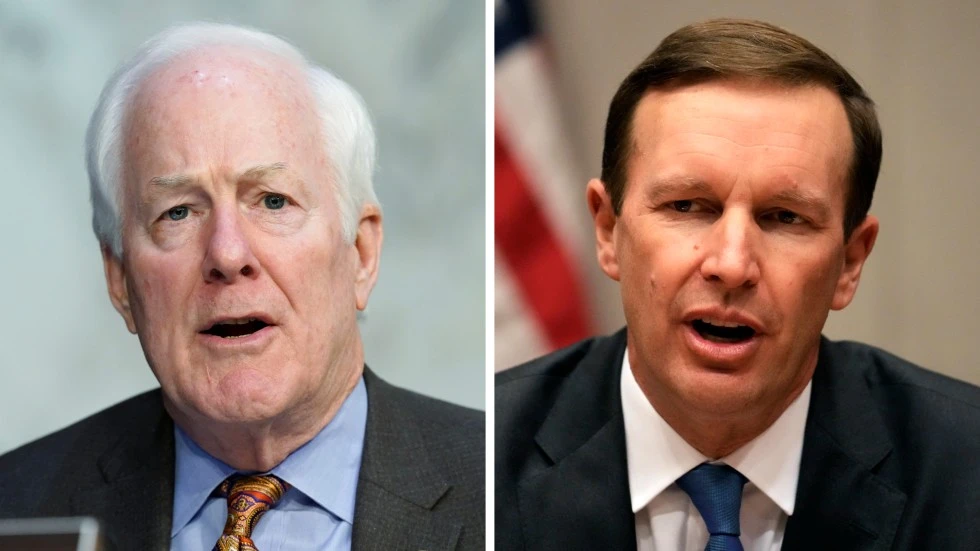

This leaves proponents of gun control with only a very narrow avenue to build a coalition with centrist Republicans in the Senate that is led by Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.). The group reportedly has discussed “red flag” laws and background checks, as well as restrictions on new gun purchases. But when Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) was asked whether he was open to making gun laws more restrictive, he replied, “Not gonna happen.”

Sen. Murphy remains optimistic that a “common sense” compromise can be reached. Yet, it will be tough sledding to get 60 senators to agree on legislation. Still, for many people the choice is clear: What is more important, the right to bear arms without limitations or the right for children to attend schools without the threat of mass violence?

Nicholas Sargen, Ph.D., is an economic consultant. The views stated are his own and do not reflect institutions with which he has affiliations. He has authored three books, including “Investing in the Trump Era: How Economic Policies Impact Financial Markets.”

Source From: The Hill